The sole copy of Beowulf is in the British Museum, as it has been since it was donated in the 18th century, and its origin is clearly in an English monastery. But the story makes no reference at all to any places in England, nor to any Anglo-Saxon kings. It is rooted entirely in the North Atlantic and Baltic coastal lands and islands.

The Germanic tribes came into written history by emerging from the north and coming down as far as Italy, Spain, and North Africa. When the migrations settled, many tribes still lived in the North. The major groups were Swedes, Danes, Saxons, and Franks, but there were many smaller tribal and national groups.

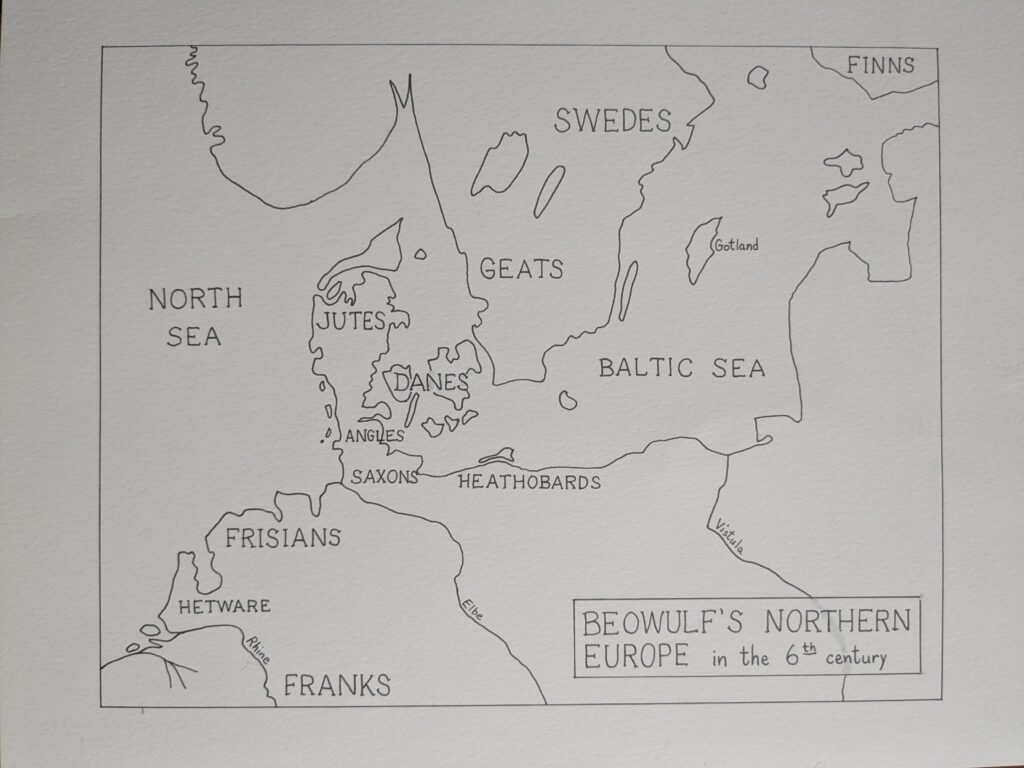

The map here has all of the peoples and places that the poem references. The Danes are on modern Denmark’s islands, but the main peninsula belongs to the Jutes and Angles. By legend, the Jutes, Angles and North Saxons settled across the water in Celtic Britain, while other Jutes and Saxons stayed behind to populate Denmark and Germany.

Tracing the identity of the Geats is not simple, partly because they don’t have a modern legacy beyond memory in place names. Western Sweden’s Göteborg and Götaland mark where the tribe once lived. Additionally, there are three very similar Germanic tribal names that may or may not be ethnically connected: the Jutes, the Gutes, and the Goths. The Goths moved south to conquer Rome, and the Gutes are marked on some maps a bit to the north of the Geats, in Sweden. Were the Geats and Jutes the same people, or were they as distinct from each other as were the Swedes and the Franks?

For modern English speakers, the name “Geat” is problematic. It sounds a bit like some ethnic slurs used in the recent past, so it feels faintly inappropriate. Does it rhyme with “feet,” the way Wackerbarth interpreted it? Short answer: no. The best approximation with a modern word is “yacht.” In Old English, a G followed by an e, i or y became a fricative that softened even more into a Y. The diphthong “ea” didn’t correspond to any of the modern readings (as in “sea” or “bear”). The letter “a” still and always meant “ah.” It was modified by the “e” only in starting with an “ey” or “ay” sound. It’s just not far off to read it as “ya.”

The letter “g” always has this flexible profile in Germanic languages. It might be a hard G as in “go;” that sound was most often retained in the northernmost tongues. It might become a sort of “gghh” fricative in middle position, and around low vowels like “o,” this could turn into “w.” When “g” it was near an “ee” sound, it might go over to “y.”

In modern English, we have accepted all of these outcomes in various words native to Old English or borrowed from Norse or German. So we see that “day” begins with “dawn,” and if you’ve learned German “Guten Tag,” you can see that the original word was “dag” (actually Proto-Germanic “dages”). Etymonline.com gives us this comparison list: Old Saxon, Middle Dutch, Dutch dag, Old Frisian di, dei, Old High German tag, German Tag, Old Norse dagr, Gothic dags.

In the same way, Old English “wain” and “wayne,” a four-wheeled cart, joined Norse “wagon,” sometimes spelled “waggon” to make sure the G stayed in place. Old English “fæger“ (Old Saxon fagar, Old Norse fagr, Swedish fager, Old High German fagar), meaning “beautiful,” saw its “g” soften to “y” when surrounded by “æ” and “e” and in modern English is noted only by the remaining “i” in “fair.” Old English “sagu,” a knife, gave us “saw” by pulling the “g” in the other direction, to “w.”

We all cope with the unpredictability of initial “g” in words like get, where it’s hard, and gel, where it’s soft. What about a name like Gilly, which appears in the Game of Thrones books? Is it hard, like a fish’s gills or a craft guild, or is it soft, like Jill or jelly? There’s really no strict answer, it could be either way.

If you can remember to read “Geat” as “Yacht,” you’re doing very well. If you forget, you’re no worse than Professor Wackerbarth.